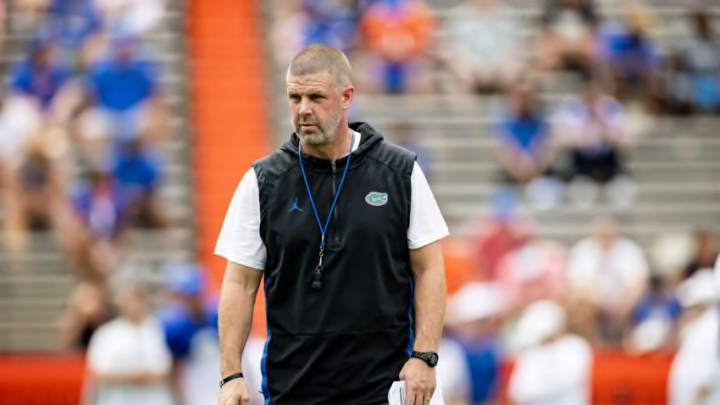

GAINESVILLE, Fla. – Sometimes when one of Billy Napier‘s players is in his office, they’ll take notice of the helmet displayed on a shelf. Napier wore it as a quarterback at Furman nearly a quarter-century ago. The Florida coach will toss it their way.

“Check it out,” he says.

What the player notices is there wasn’t much to the inner-workings of college football helmet, circa 2001, which is why Napier is so candid with his players about his concussion history – “Had several of ’em, actually,” he says – and why the latest data on player safety has a vital role in the day-to-day operations of the University of Florida program.

Some of the data, not yet made public, were eye-opening. The conclusions, however, were not.

“The sooner a player reports concussions symptoms, the sooner they’ll likely get back on the field,” Dr. Allen Sills said.

Sills is the National Football League’s chief medical officer. A professor of neurological surgery as well as founder and co-director of the Vanderbilt Sports Concussion Center, he’s one of the preeminent names in all of sports medicine, which made his visit last week to the Heavener Football Training Complex – and his “Innovations to Make the Game Safer Presentation” – a must-see event and fountain of information for Napier, his coaches, support staff and Gators’ sports medicine personnel.

“The NFL is on the cutting edge of player safety and we always try to stay on top of that,” said Paul Silvestri, senior director of sports health and performance for UF football. “To have these kinds of discussions with someone as impressive as Dr. Sills, I can’t put a value on it.”

The NFL has implemented a slew of rules changes this decade in the name of player safety, including two high-profile alterations last week; one that will make kickoff returns both more viable as game-changing plays while also reducing risk of high-speed collisions and another banning a dangerous tackling technique known as “hip-drop” that resulted in lower body injuries 6.5 percent of the time it was used last season.

The changes were finalized during the NFL owners meetings in Orlando, after which Sills zipped up the Turnpike to check in with the Gators as part of UF’s partnership in the NFL/NCAA Research Consortium.

UF, along with Vandy and the universities of Georgia and Pittsburgh, joined the consortium in 2022, a year after the universities of Alabama, North Carolina, Washington and Wisconsin initiated a study that uses mouth guards instrumented with sensors to analyze the frequency and severity of impacts in games and practices.

Though today’s football players, at all levels, have grown up with concussion protocol, the gathering of data and innovations in player safety is an unceasing endeavor.

Take the padded guardian caps that fit over helmets. They’re now a fixture at practices at both the NFL and NCAA levels. According to Sills, in each of the last two years concussions have dropped nearly 50 percent over the previous season during practices.

“And not just because of guardian caps,” Sills said. “It’s about coaching players not to use their heads.”

Interesting stat, partly acquired through mouth piece devices: Teams with offenses that registered the lowest helmet impact data averaged more yards per carry than teams that registered on the higher end of helmet impact data.

“It’s awesome to be able to see data that shows being safer leads to better performance,” UF team physician and study principal investigator Jay Clugston said.

While coaching at Louisiana, Napier visited the Los Angeles Rams and got a close-up look at how things were done at highest level. Napier brought some of those pro tactics back to Lafayette, La. – such as load management and a “ramp-up” (from 90 minutes to 120) in early training camp practices, both of which lead to fewer soft-tissue injuries – and eventually with him to Gainesville.

While the NFL has across-the-board rules for all 32 teams – and a Collective Bargaining Agreement that enforces those rules – the NCAA has too many leagues and too many schools for uniformity.

So it’s up to the individual program.

“The NFL tells its teams, ‘Here are the rules, backed by the data, and it works,’ “Silvestri said. “[NCAA] doesn’t have that, but it doesn’t stop an institution from making change and getting ahead of the curve after seeing, ‘Yeah, the data does work.” Coach Napier is great with that stuff. He’s great at listening and looking at data and making change.”

During his presentation in Orlando, Sills said he got a question from a prominent, very successful head coach, who said he was all for player safety but reminded the league’s CMO that he also was under pressure to win.

Sills’ search for the best way to accomplish both is ongoing, with the Gators doing their part.

“I was a player, right? For me, because of my experience with concussions, it’s an important piece,” Napier said. “My dad was a coach. I got two brothers who are coaches. The game is about the players [and] anything we can do to make our game safer – rules changes, equipment changes, collection of data – I’m on board with that.”

Be the first to comment